"Columbia, for all its supposed liberality, is segregated."

What we find when we look behind the curtain of Ivy revisionist histories.

One of the lesser-known things about my Instagram feed, focusing as it does on “Ivy” style, is that it has very few photos from Ivy League colleges and universities. The fact is that (with very few exceptions) I use publicly available digitized archives to find my photos, and most Ivy League schools keep their histories out of the public eye. However, thanks to @take_columbia, I was able to look through the 1967 Columbian yearbook. It had a treasure trove of tweeds, duffel coats, oxford cloth button-down shirts, and rep ties, but it also had something that caught my eye as soon as I saw one of @take_columbia’s quick snapshots of a couple of pages in the middle of the book:

Columbia is a really interesting case when it comes to the Ivy League in the late 1960s; because of its place in the middle of New York City, because of its student makeup, and for myriad other reasons, it (unlike other storied Ivy schools) became a hotbed of activism in the Vietnam War era. What was the place of the Afro-American Society (more correctly known as the Students Afro-American Society, or SAS) in this larger milieu of Columbia activism? The yearbook page for SAS continues:

Okay, so a lot to unpack here. J. Press! I think my first impulse as someone who loves Ivy style is to foreground that mention — I’m sure Richard Press would love it, too. Every February, and every few months in-between, we get the usual “Martin Luther King bought a tie from J. Press,” “Sidney Poitier wore navy blazers,” “Miles Davis bought from the Andover Shop” stories that superficially serve to increase the diversity of the Ivy canon but more meaningfully serve to congratulate ourselves that Ivy has always been inclusive. So, we Ivy fans love taking any opportunity that comes around to bolster that image of a democratic, color-blind Ivy style.

Of course, color blindness isn’t equity, even if it’s equality. Digging deeper into the SAS blurb, we discover some troubling things. The mentions of a “fighting gang” and “Harlem punks” play into stereotypes about Black Americans; the emphasis on J. Press, “cogent thoughts,” and the “glib, perceptive” Belt, who is “beautifully-dressed,” all serve to set Columbia’s Black students apart from the usual inarticulate Negro or from the dangerous Black Panther.

Doing a little more digging into SAS, I came across a supplement to the Columbia Daily Spectator from April 26, 1967, titled “The Negro at Columbia.” Some of the articles in the supplement shed light on aspects of the yearbook blurb for SAS.

Something glossed over in the yearbook is just how extreme a minority Black students were at Columbia in 1967. The yearbook blurb takes pains to point out that SAS is not a Black-only student organization, but also includes “a spectrum of colorations,” such as “wombed whites from Great Neck.”

SAS did allow white students to join, as detailed above, but to my mind, the decision smacks of survival: elsewhere in the supplement, there’s a description of Columbia administration officials, as well as the student body more generally, accusing Black students of “resegregation” by insisting on Black-only spaces, and it’s easy to imagine a charter or funds for SAS being denied if it excluded white members.

The crazy thing, of course, is that the Black population at Columbia was so small. Another passage from the supplement states that “until this year [1967],” the Columbia Black community '“maintained a somewhat tenuous existence, due to sheer lack of numbers. There were only 35 black students in the College last year, but there are 36 Negroes in this year’s freshman class alone.” What threat could these Black-only spaces possibly have held to the larger population? The supplement provides one likely answer: the college’s own liberal self-congratulatory attitudes.

Columbia viewed itself as progressive for admitting Black students and for running “exchange programs” with predominantly Black schools in the South; if these Black students were dissatisfied with Columbia when they arrived, then, it was surely much easier to blame them then to examine Columbia’s own policies and methods critically, especially if student response indicated that those policies would have to be deemed largely a failure.

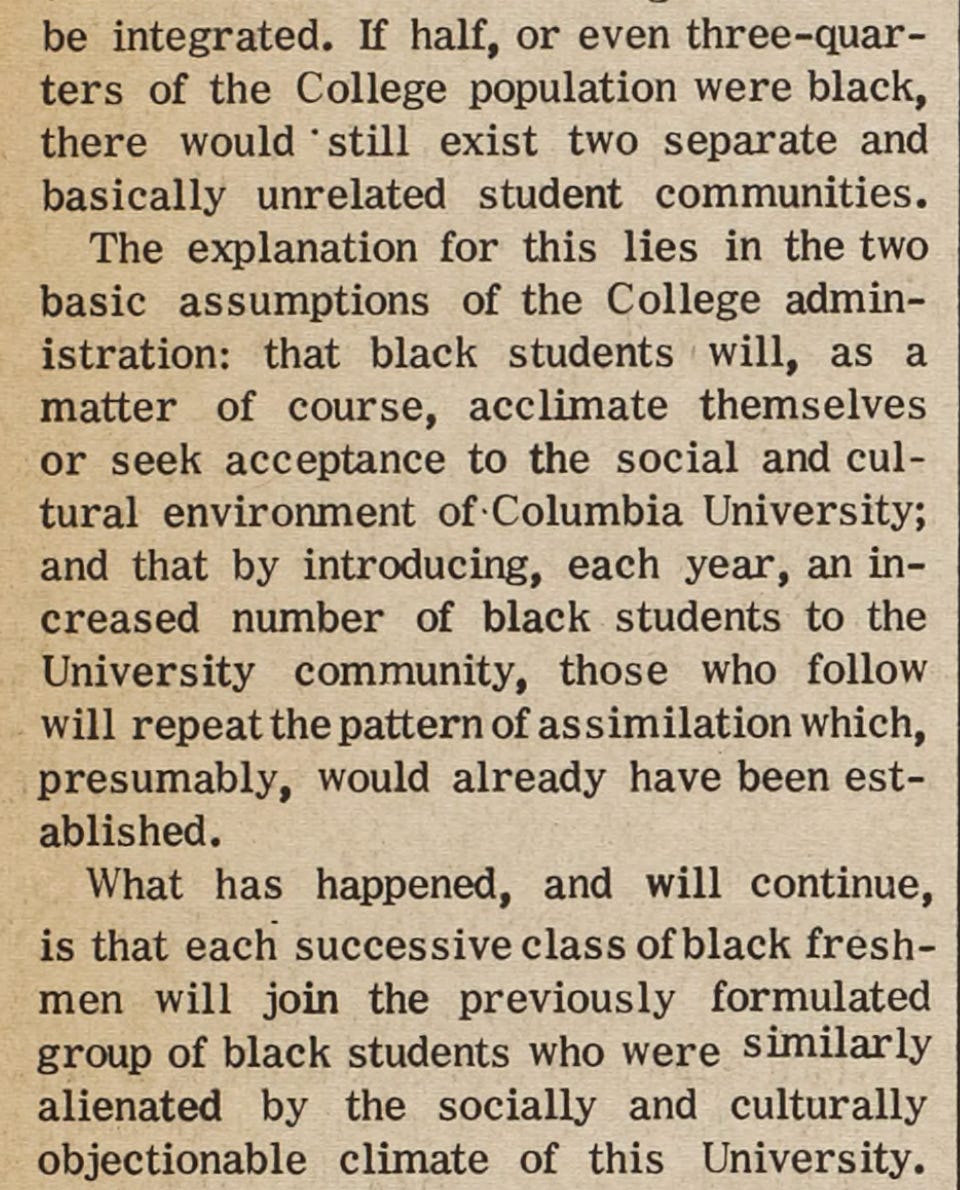

In fact, as the supplement describes:

To return to the SAS yearbook blurb, I feel that its mention of “a tutorial group” that “aids some Harlem punks” takes on a different tone when we know the larger context: that Columbia’s Black students, who weren’t from the prep school background available to white students, were often not well-prepared for Columbia, socially or academically, and that they felt Columbia itself was derelict in its responsibility to tutor them so they could succeed and actually fulfill Columbia’s lofty goals of racial inclusion. Instead, Columbia seemed satisfied to admit Black students and wash its hands of any further issues those students may have had. Is it surprising, then, that Columbia’s Black students would want their own spaces?

This demand for Black spaces on Black terms is very reminiscent of the rhetoric of Stokely Carmichael, who wrote in a 1966 pamphlet entitled “What We Want” that

One of Carmichael’s core arguments was that this insistence on Black equality on Black terms is often weaponized against Black civil rights by white communities in the name of integration — that Blacks’ insistence on success on their terms was not equality, but separatism:

Carmichael, a man who wore beautiful Ivy and Ivy-adjacent clothes throughout the 1960s, was also closely associated with the Black Power movement and the Black Panther Party. Like the students of SAS, he was not a Black Panther “in appearance,” but also like the students of SAS, he was very much one in rhetoric. As the Columbia supplement describes,

And indeed, Black students at Columbia were far from enthusiastic about the college’s goals:

The yearbook blurb for SAS presents it, somewhat humorously, as a Black student organization which provides a forum for greater connection and understanding between Black and white students, populated by students in J. Press tweed (see, they’re just like us!). The superficial “inclusive Ivy” narrative supports this, because J. Press’s PR department wants more examples of people wearing these clothes who weren’t blatantly racist, and blogs like Ivy Style want to be able to include more Black History Month content to show who egalitarian Ivy is (“Nobody has ever done for the black community what Christian Chensvold has done”).

I support this push for more diverse Instagram content and more Ivy icons of color being included in the canon. But I push back on a rush to include these new faces without really examining the ways white Ivy closed the doors on them at the time, and the ways our rush to diversify the Ivy canon can paper over those struggles, letting ourselves off the hook in the process. While Sidney Poitier and Miles Davis are both great examples of Black celebrities in Ivy (although, as I’ve discussed before, their own relationship with Ivy clothes and the dominant white culture can stand more critical examination), Black History Month was established “to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.” Highlighting famous actors and musicians adds a lot to the Ivy narrative, but we shouldn’t exclude the experiences of students as well, who wore the clothes without the fame.

Thanks to @take_columbia for sharing his Columbian scans with me and allowing me to use them in this essay!

Did you enjoy this post? Do you want to stay up to date on more longform content from Berkeley Breathes, like interviews, additional #ownfind images, and essays? Subscribe and get me delivered straight to your inbox, for free! And if you do subscribe, tell a friend and spread the word. Remember, it ain’t that serious! 🥂🤝✌️