Who Are the Proles, Anyway?

As Ivy, and #menswear at large, haltingly begins its long overdue conversation about diversity and inclusion, one way we perpetuate exclusion seems to be flying under the radar: class.

I saw a comment recently from an Ivy fan, complimenting J. Press for “keep[ing] a candle lit for the American Dream, with an easy, egalitarian style that works for anyone who cares to try it on.” I often write about race here on my feed, and the way that, in fact, many seem to prefer it (consciously or unconsciously) if only white people “cared to try it on.” The mention of the “American Dream” adds more layers of complexity, of course. Theory and practice are very different things, and while the Declaration of Independence proclaimed that “all men are created equal,” the reality was very different (see: slavery, women’s suffrage, indigenous genocide). Many get defensive about this — when Ta-Nehisi Coates critiqued the American Dream in “Between the World and Me,” professional well-actually-sayers like David Brooks rushed to protect it: “[A] dream sullied is not a lie. The American dream of equal opportunity, social mobility, and ever more perfect democracy cherishes the future more than the past.” Brooks begs two questions, however: first, that the Dream was ever unsullied in the first place, and second, that its promised future will ever be allowed to arrive by those with a vested interest in the power imbalances of the present. We live in a world where brands see a value in trumpeting their commitment to racial and gender diversity (and, increasingly, sexual and gender orientation) — their statements may be sincere, they may not be. But they exist, and that’s a start.

One flaw in Ivy’s (or trad’s, or #menswear’s — pick your poison) “egalitarian” image I absolutely never see examined, even in a cynical or cursory way, is class. That doesn’t mean I never see it mentioned. One passage from Paul Fussell’s 1983 book “Class” has a tendency to creep into discussions of Ivy, particularly how clothes should fit: the one describing “prole gape,” when “the collar of the jacket separates itself from the collar of the shirt and backs off and up an inch or so.” Prole, of course, means a member of the working class. Fussell takes pains to point out pointing fingers at “prole gape” is not “reactionary”: “jacket gape afflicts the far left as well as the far right.” Instead of political orientation, Fussell uses “prole gape” to identify intelligence and education. Writing of the Mel Gabler’s 1982 appearance on Firing Line, Fussell sniggers at Gabler’s mispronunciation of the word “promiscuity” and notes that Buckley “gently” corrects him “so that the audience would know what the poor ass was talking about.” Buckley’s correction is gentle — he simply repeats the word with the right pronunciation and moves on — but Gabler’s mistake was still perfectly comprehensible without it. I use mistake with a caveat. As an English teacher, part of my job is teaching vocabulary and grammar. However, as schools, and the world they exist in, becomes more inclusive and aware of positionality, the standards of “correct” English, especially in speech, have been called into question. From Gabler’s comment and the wider context of how he speaks in the Firing Line episode, I do think he didn’t know the “correct” pronunciation of “promiscuity.” However, he also has a strong Texas accent that affects his pronunciation of other words, like “government.” Fussell is potentially engaging in linguistic discrimination, treating Gabler is inherently dumber because of his Texas accent; Buckley is, too, by stepping in to correct him in front of an audience. Ivy fans swoon over Buckley’s own lockjawed accent, as they do with Plimpton’s patrician voice or the Kennedy’s Boston Brahmin accents. Yet I suspect many of us unthinkingly nod along with Fussell when he ties Gabler’s incorrect arguments to his Texas background and accent.

At one point in the program, Buckley asks Gabler if he is accusing a textbook of being “factually inaccurate, or tendentious?” Gabler pauses, then says, “Well, you’ve hit me with a word I don’t even know.” I think Gabler and his crusade were very wrong and harmful, but I also believe that Buckley’s use of five-dollar words and his “gentle” corrections were explicit strategies he used to catch guests off guard and give himself the rhetorical upper hand, either in one-on-one debate or in the audience’s mind. Gabler was a former oilfield worker, Army Air Corps veteran, and Esso clerk, and William F. Buckley was the son of an oil developer, was educated in France and England, and was a graduate of Yale. Gabler was wrong, and to many more comprehensively educated people, the temptation is strong to dismiss him as an idiot, as Fussell (Pomona, Harvard) does. Perhaps that’s fine. But I think it’s not fine to then connect that snobbishness to the way clothes actually fit. Fussell notes that even if Gabler “had not, with complete confidence in his unaided powers, delivered repeatedly this prole mispronunciation, his perceptiveness and sensibility could have been inferred from the way his jacket collar gaped open a full two inches.” No, it could not have been, and asserting that it could is, indeed, reactionary — a desperate clinging to class markers and an enforcing of “caste marks” (Fussell’s phrase) in clothing to disparage those less privileged than others.

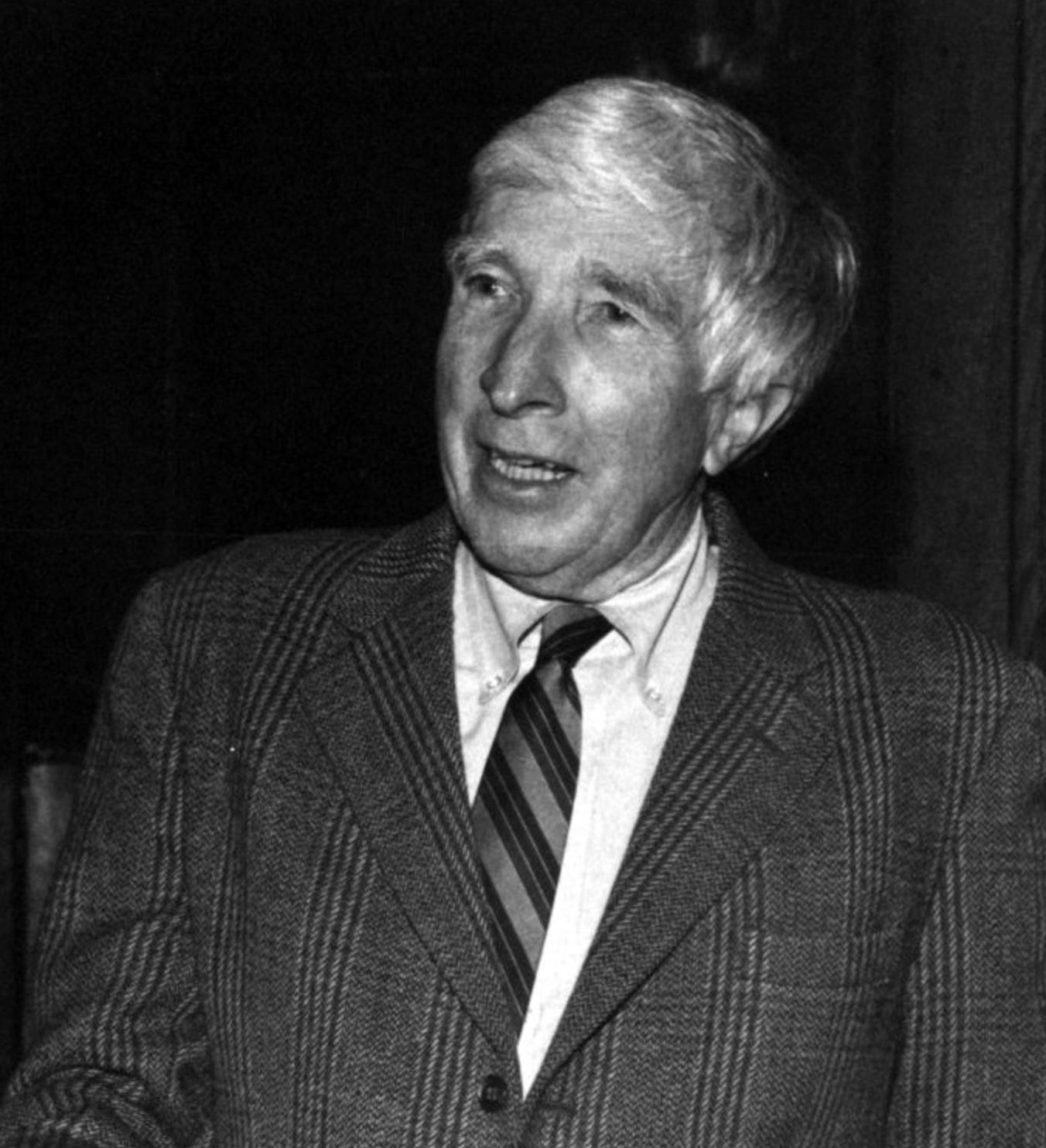

It’s all bullshit. That Gabler was indeed wrong, and was indeed less educated than Buckley, does not prove Fussell’s argument, but rather indicts him as a cherry picker. Look at the photos in this post. All are of educated Ivy style icons, ones we would never for a moment consider calling “proles.” In fact, I bet we’d try to defend these men against the “prole gape” accusation — “Look, his jacket is buttoned!” (So was Gabler’s.) “He’s sitting down!” (So was Gabler.) Really, it doesn’t matter. It’s not about accuracy, it’s about snobbery. When it comes to the prole, there are no excuses. As Fussell notes smugly, “Buckley’s collar, of course, clung tightly to his neck and shoulders, turn and bow and bob as he might.” Of course. After all, the difference isn’t cost — Buckley famously bought suits at JC Penney — it’s class. Yet would we diagnose Updike’s gapped collar as an example of failing to “recognize a class signal”? Or, for that matter, would we do so for Buckley himself? The “prole gape,” perhaps, is really more about the biased eye of the beholder than the deficient class education of the wearer. It’s not really about who is working class, middle class, or upper class — it’s about who is doing it wrong and who is doing it right, and “class” is simply a handy weapon to use against the people doing it wrong, and a handy pat on the back for those doing it right.

People love to talk about how the G.I. Bill erased class differences in Ivy style. Oh, really? Paul Fussell apparently didn’t get the memo. Ivy, and #menswear more largely, is anything but egalitarian. Sure, it keeps the American Dream alive — it’s a style that used, and uses, a lot of minority labor to create the uniform of the carefree elite, who then marketed it to the everyman as a ticket to the upper class and laughed at them behind their backs when they got it wrong. It likes to show that it’s progressive by filling its brochures with POC, and by being down with sneakers and hip hop and basketball (we can unpack that later, but it’s not great, Bob), but don’t worry, it still has lots of Wes Anderson and prep schools to balance all of that out. Lisa Birnbach wrote in the opening to the Official Preppy Handbook that “Preppies don’t have to be rich, Caucasian, frequenters of Bermuda, or ace tennis players.” But they do have to look like they are, and that ain’t cheap. I wasn’t able to find a single picture of Daniel Patrick Moynihan with a gaping jacket collar. Raised in underprivileged Hell’s Kitchen, he ended up at Tufts and LSE, and was ultimately worth between $1 and $5 million. In 1983, when he declared his net worth as $355,372.66 ($938,433.58 today), he earned over $100,000 (in 2021 dollars) in speaking fees alone, when the average American’s income was a little under $65,000 (in 2021 dollars). Ivy discussions of small wardrobes or “thriftiness” often favor buying fewer but much more high-quality (read: expensive) items. Under one Ivy-Style.com post on small wardrobes (that positively quotes Tom Ripley gaining a sense of self-worth from a Gucci suitcase), F.E. Castleberry commented, “I too love going in each season and trimming up my wardrobe down to the essentials and staples… and giving away/selling the excess. I practice a rule: ‘If I haven’t worn it in a year, I pull it.’” Of course, the only way to be able to trim your closet each year is for it to grow again in between; regularly donating items that haven’t been worn in a year assumes an unchanging level of excess. On another post, about building “the ideal trad wardrobe,” Caustic Man (who seems to have blocked me on Instagram, which is an enormous and heartbreaking loss) writes, “If you adopt the rote Ivy look in a whim, or at the drop of several thousand dollars, you will appear soulless and destitute of moral position. Rather, learn to appreciate the context in which the style created itself.” Another reader points us to official J. Press brand spokesman Richard Press’s list of “10 Ivy League Wardrobe Essentials,” all of which can be purchased at Squeeze for the tidy sum of $4,300 (that’s more than three stimulus checks, by the way). In a recent essay (“essay”) for Artful Living, David “Sneakers Make Men Look Like Boys” Coggins writes, “Edward Green and John Lobb are… good places to start.” Also on his list of “5 Shoes Every Man Should Own”? Famously versatile, long-lasting, and budget-friendly Belgians.

The argument can be made, of course, for Fussell’s “prole gape” as a celebration of class mobility rather than an attack on it. “The distinction I’m pointing to,” Fussell writes defensively, “is not one between the tailored clothes of the fortunate and the store clothes of the others, for if you try you can get a perfectly fitting suit collar off the rack, or at least have it altered to fit snugly. The difference is in recognizing it as a class signal and not recognizing it as such.” Surely, anyone can reach this bar of class awareness. But how is that recognition conferred? The Ivy Style commentariat have called it “good breeding” (a nice way to claim the enlightened peasant for the aristocracy, isn’t it?). On Instagram, it’s more likely to be phrased as “if you know, you know.” And how is this knowledge gained? Via blog posts that teach the caste marks every good Ivy dresser should know; via Instagram posts with twenty brand tags, pointing you to oh-so-accessibly-priced brands like Drake’s (ties starting at $225), Sid Mashburn (trousers for only $350!), and Alden (shell cordovan, the only acceptable leather for a Real Ivy Fan, can be yours for just $782); via vintage “dealers” who talk about their “clients” and disparage more affordable options like eBay; via checklists in books like the Official Preppy Handbook (collect ‘em all!); via the fetishization of celebrity style icons with endless (or even better, film studio-supplied) wardrobes, or “thrifty” ones like Prince Charles, who is endlessly applauded for having his tax-funded staff maintain his £2500 shoes. And if you fail, then congratulations — you’re a prole. If the better you dress, the worse you can behave, then the burden of good behavior that falls on the unenlightened is heavy indeed.

Great article. I think that there is a subtle semantic distinction between Ivy League and Ivy Style. One is for the established upper/upper middle class, the other is more democratic. Richard Press mentions this in one of his articles in the J.Press threading the needle book. He claims that some young men were referred to as shoes, "white bucks" I take where the Ivy League alpha males, and "weenies" were the weejun wearing undergrads who may have been G.I bill admissions or not.

Please forgive the grammer mistakes etc.